Magic Island Literary Works

Magic Island Literary Works by Larry Mild

| Home | Select Books From Spread | Authors | Contact Us | Author Interviews | Monthly Blog |

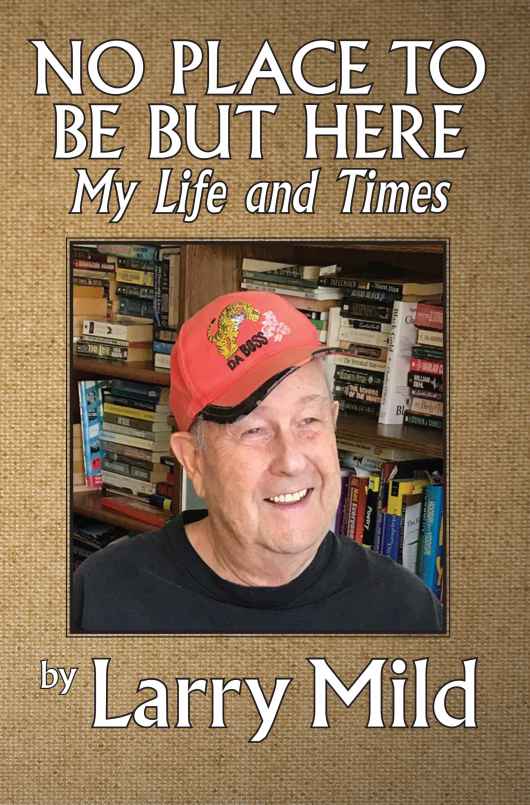

Follow Larry Mild's life as the introverted, chubby youth struggles through his formative years to eventually find success and fulfillment as a technician in the U.S. Navy, as a digital design engineer, and, finally, as a mystery author. Track his successes and slips as he attempts to deal with every challenge and blessing tossed his way. It is not only his own story, but that of his family. Join him as he tells how his two wives, three children, and five grandchildren have shaped his life as much as he has molded theirs. Tragedy is certainly no stranger as he deals with death, cancer, murder, and global terrorism, not only on the written page, but in his own life. Learn about the many unusual positions he's managed and some of the design projects he's brought to fruition. Trace his path to becoming a mystery author. Travel with Larry and his wife,Rosemary, to Hawaii, Japan, China, Italy, New Zealand, Australia, Cambodia, Thailand, the United Kingdom, Israel, and Egypt with color pictures. |  ISBN:978-0-9905472-1-1. Magic Island Literary Works (Spring 2019) |

To let Larry know what you think of

No Place To Be But Here, My life and Times

E-mail us at:

[email protected]

|

Buy autographed trade paperbacks at author's discount price: $21.95 + $3.85 shipping. E-mail us at: [email protected] |

| Enjoy a sample chapter of No Place To Be But Here, My life and Times by Larry Mild | |

Chapter 1

An Unexpected Beginning

9/20/32

Six years and three months after the arrival of my brother, George Leon Mild, a second delivery arrived at Grace-New Haven Hospital for my parents, John Mild and Hilda Eleanor Glueck Mild. The auspicious date was September 20, 1932. Some years later, that lengthy gap in sibling arrival time started me wondering whether I, Lawrence (Larry) Milton Mild, was a planned or an oops event. I also learned they were anticipating a Lois Mild, perhaps a second disappointment. Even so, I never felt there was a lack of love or caring among the four of us. Fact is, they didn’t return me to sender. The separation in brotherly years soon labeled George “Big Brother Babysitter” and me “Larry the Brat,” a status neither one of us ever wanted, but wound up experiencing anyway. A few days after my bursting on the scene, I traveled to a modest, pale green, two-story home at 157 Spring Street up in the hill section of New Haven, CT.

Passing the diapering, feeding, toddling, and preschool mischievous ages with flying colors, I emerged a shy, chubby, and tall kid who wore short pants in the summer and knickers and knee socks in the winter. Oh how I yearned to wear long pants like the big (older) guys. My size was always stout and my knickers were noisy due to the rubbing of corduroy on the inside of the legs. You could always hear me coming with my infernal zizz-zizzing sound. A rip or a stubborn stain in any article of my clothing, accidental or not, usually warranted a stiff scolding from Mother. Once past the Mommy stage, it was always Mother in the early years, because “Ma” and “Mom” were undignified, “sounding too much like a billy goat,” she insisted.

I attended Horace Day Elementary School slightly over one city block away from home. The student furniture comprised row on row of attached folding seats in front of wooden, hinged, flip-top, desks supported by wrought-iron pod-like legs that were screwed to the floor. There was always a two-inch hole in the right corner of each desktop for an inkwell. Each row of desks and seats grew in size and height from the front of the room to the rear, to accommodate varying student packaging. So guess where oversized Larry wound up. Yep, in the last row lest my knees be squished and bruised. One might think this afforded a child some measure of invisibility during hands-raised class questions. Yep again, that is, when everyone among a sea of anxious hands knew the answer, but a definite nope when no one knew the answer. The last row became vulnerable then and I had trouble sometimes delivering the tough right answers. I had my share of bright and lucky answers too; I certainly wasn’t a dullard.

The schoolrooms were spacious—wide with high ceilings and eight-foot-high windows. At least two walls were functional in each room. One of them was covered in bulletin boards and another in dusty wood-framed, black slate, blackboards that required routine washing. Chalk sat on a narrow ledge below the blackboards alongside erasers, whose cleaning required battering a pair together, so that the impact produced a massive cloud of chalk dust from both erasers. This cloud was both a source of humor when its dust reappeared on someone else’s face and clothing or a form of punishment when it reappeared on your own puss. Some found the practice a good excuse to miss some class work. Others thought the assignment was a teacher’s reward for good behavior.

Did I mention the earliest desktop peripheral—the glass inkwell that occupied the aforementioned hole in every desk cover? They were delivered to each desk only during penmanship exercises and returned afterward. Yes, we actually used them with our wooden dip pens, a mere step above bird-feather quills and only used by show-off calligraphers today. Dip and scratch (from the noise they made) pens were five-inch, tapered wooden stems with a metal nib or pen point stuck in one end. I want to blame my growth spurts and poor small motor skills for the unintelligible mess that evolved from my penmanship classes. Teachers were not always willing to decrypt much of my scribbling, so my grades suffered for it even then. Being classroom-shy didn’t help the grades any either. My shyness I attributed to my mother’s strict discipline and her philosophy “Children are best seen and not heard.”

Getting back to those eight-foot schoolroom windows. In second grade two of them came crashing in on our classroom due to the high winds of the great hurricane of 1938. Everyone knew there was a storm afoot, yet no one dreamt of its intensity. And who knew of the early storm warning systems that are in place today? Luckily, we were all hunkered down in a central hallway, with the doors to the surrounding rooms shut, so to the best of my knowledge, no one was injured. During the quiet of the storm’s eye, my father came to the school to rescue me. I still have a child’s faded vision of branches and leaves everywhere, but the uprooted trees lying across impassable roads and across sidewalks and yards stayed with me. Mostly, I remember the demise of a giant elm that once towered over the front of our house, graciously lending us its shade and cool. You see, only some theaters had air conditioning in those days, so nature’s cool was quite important. This tree’s roots continually tore up our front sidewalk and kept my dad busy cutting them back and patching the walk with concrete cement. Well, the tree finally had its measured revenge and tumbled straight across Spring Street, stretched to the opposite walk, and bent to rest on someone else’s front stoop, a serious shoal to through-traffic. It could have fallen toward our house and devastated most of our home, but it didn’t.

A lattice structure attached to the backyard boundary fence was always thick with grape vines. Late in the growing season my parents made a juice and sometimes a wine from the grapes and, at the end of the process, bottled it in our basement. I couldn’t tell you much about either the grape or the wine, but my discovery of the bottle-capping device became a source of mischief for me. Put the cap on the bottle and pull down the lever. Pull off the cap with a bottle opener. Hey! This is fun—try another—and another—until a whole carton of caps became a lost cause on the basement floor. After my mother’s call down the stairs: “What are you doing down there?” and my casual reply: “Nothing”—I literally caught hell for my folly.

We lived on the first floor of the two-story, house on Spring Street and rented out the second floor. The house had a finished-floor attic which we used mostly for storage. One small window in its rear accessed a clothesline strung from the third floor to a telephone pole in the backyard. A screened-in front porch ran across the narrow frontage of the house. A door outside the porch led to the sec-ond floor, and a door inside the porch led to our dining room. Two smallish rooms shared the front of the house, the living and dining rooms. A door off the dining room led to the kitchen. To the left of the kitchen lay a tiny hall accessing two bedrooms and a lone bath.

We had a long cement driveway that ran the length of the house and broadened to the width of the property line beyond— ending with a four-car garage that we rented out. In my earliest memory we had a car, but for the life of me, I couldn’t tell you its make and model. I must have been four or five years old when I climbed into its driver’s seat and made-believe I drove it all over town. As with most of my mischief, I was caught red-handed at the steering wheel and heavily scolded for, would you believe it— breaking the car. To reinforce this accusation, the car was taken away the next day and never seen again. It was many years later that I learned that my mother had had a nervous breakdown and was no longer allowed to drive. She never drove again, and as far as I knew, my father never drove at all. He preferred public transportation which was mostly trolleys at the time.

Another white lie proffered by the family concerned my father’s older sister, Aunt Fanny, who had a big white house on a hill in the Westville section of New Haven. Three words told all— she was a cheek-pincher extraordinaire, and my plump cheeks were just too much for her to resist. Most of the time I dutifully bit my lip and endured the pain, but on one occasion, she went too far, and I told her off in no uncertain terms. “That hurts! Get out of my house and don’t come back!” She left the house, and I didn’t see her for at least ten years afterward. I was led to believe this was because of my outcry. Again, many years later I learned the truth. My mother and Aunt Fanny had had their own skirmish on a totally different subject. The family did reconcile with my aunt some time after that.

Though these (the 1930s) were the years of the Great Depression, my father continued to work regularly, thanks to the carpenters’ union hall and his reputation and persistence. Money was tight, but there was always food on our table, and our clothes were always clean and in good repair. But jobs were scarce. Many men were out of work, and due to the reigning culture of the times, women were restricted to a scant number of vocations. Beggars often came to the door for handouts. We did what we could.

Street vendors, a common sight in the 1930s, are almost unheard of today. A fish monger pushed a two-wheeled, wooden cart from behind, holding onto two wooden handles. Under the double-hinged wood covers lay the fish packed in ice. A pull-spring scale and tray, suspended from a pole arm, ensured good product measure, and a conical-shaped metal horn’s tooting announced his arrival. A man with a smaller, hand-driven cart and a large emery wheel driven by foot pedals could sharpen scissors and knives or even repair umbrellas. Fresh vegetables came down the street direct from the farm on a horse-drawn wagon. Trails of horse poop in the street were common. And there were the rag men who bought scraps and leftovers from just about any project. They paid pennies, nickels, and dimes for weighed old clothes and metal scraps—even my father’s old bent nails. The proceeds were always mine—my first access to personal spending cash. The largest personal allowance I ever received from my parents was 25 cents per week.

Aunt Catherine, my mother’s younger and unmarried sister, lived with us from my earliest days in the Spring Street house until her marriage. Her bedroom was a small footprint alcove off the dining room, a space under the external stairs that led to the second-floor rented apartment. With room for a twin-sized bed and standing room only, my dad installed a built-in dresser under the bed and a pair of curtained glass doors for the thirty-year-old’s privacy. It also had one curtained window to the outside. When I was approximately eight years old, she married Uncle Meyer Rubenstein, a fun and lively sort some years older than her. They lived in New London, an hour’s drive from us. Eventually they had two sons, Richard and Lenny.

Afterward, I spent a few weeks each summer with them. One summer’s day we all went swimming at a nearby pond—that is, they went in to swim, and I dangled my feet over the edge of a pier at one end of the pond. Uncle Meyer came back onto the pier and asked me if I wanted to learn how to swim. When I answered in the affirmative, he literally picked me up and dropped me into the drink. Why would he do such a thing? With the question sitting on my mind for a split second, I began floundering, my hands flailing, my chubbiness trying its best to contribute to my minimal buoyancy. Finally, I looked up at Uncle Meyer and saw him slowly, methodically, and repeatedly going through the essential motions of the crawl. It didn’t take long before I got the message and began to follow suit. Using arms only, I reached the pier, and he leaned over and pulled me from the water. He apologized for the surprise launch and spent a good deal of time refining the arm motions and teaching me the kick. In one terrifying lesson, I had learned to swim.

Although many cooperative grocery markets flourished in the times, the concept of the supermarket remained somewhere over the horizon, a thing yet to come. More common were the small, independent, sole proprietorship and partnership businesses, i.e., the family business era. The interaction between seller and buyer was far more personal then than it is today. For example, my father used to take me a few blocks away to Meyer’s Bakery (not my uncle) where, after a jovial conversation, the owner would take me into the back room to watch the crullers being twisted or the jellys and creams being injected into the donuts. We would always return home with a large (12-inch-round) flowered or seeded cornrye bread or pumpernickel bread—best eaten with sweet unsalted butter. Sometimes there would be bagels or bialys in a second bag, another treat.

Not only the bakery, but the kosher delicatessen too. I wish I could remember that kindly man’s name. Whenever I tagged along to the store, he came out from behind the counter to reward me with a small chunk of halvah—a ground almond cake. When it came time to purchase new dill pickles, he’d hand me the large tongs and let me bob and fish in the wooden barrel for them myself as he held the waxed paper to receive them. The salamis and pastramis were my favorite deli meats, and if I was lucky, he’d hand me a scrap from the overage. If my mother went to the dairy case, there was a chance she would buy some pot cheese, the main ingredient for my favorite, her cheesecake with the braided top. Pot cheese came in a large round wooden tub that faced forward on a tilt in the glass case and was dispensed with a large wooden spoon. Slightly drier, much airier (lighter) than cottage cheese, pot cheese made the best cheesecakes ever and yet is almost unheard of today.

Quintos Fireworks store, several doors away from this deli, was the site of a major explosion and fire started by the casual toss of a lit cigarette into the outside display. The ensuing fire consumed most of the surrounding block, but for some unknown reason and our good fortune, it had spared the deli.

The price of a loaf of Wonder Bread was 12 cents; a pound of butter, 25 cents; a half-pound of salami, 30 cents. A child’s haircut was 25 cents, and an adult cut was 75 cents. A Saturday matinee cost the better part of a dime (9 cents), leaving you enough for a penny’s worth of loose candy. Candy bars cost a nickel. Saturday matinee fare at the movies usually meant a pair of older double features or a single new feature and a string of short subjects (Superman, Buck Rogers, The Green Hornet, The Three Stooges, and three or four animated cartoons.) If you were lucky, sometimes a comic book, with the corner cropped to prevent resale, was thrown into the bargain. Adults had their own bargains on Tuesdays or Thursdays and could collect glass tumblers or even dishes and the like. Gas stations had their own promotional give-aways in tumblers and cups.

In the 1930s and ’40s polio threatened the nation and, as yet, no cure had been found. Spending time in an iron lung to breathe and using double mirrors to see, was a very scary thing. People deserted organizations and clubs and avoided crowds. Kids wore camphor bags around their necks that stank to high heaven, but they did keep friends from getting too close. Even movie theaters suffered a decline in patronage.

Television hadn’t arrived on the scene yet. Radio and newspapers were our main source of information and entertainment. Our main radio was a piece of maple furniture, standing at least three feet high and two feet wide; it stood in a corner between the upright piano and the sofa. The geometric floor space created by the confluence of sofa, radio, and upright piano was mine. I’d curl up there with my back against the sofa and my toes propped up by the piano. Smack-dab in the middle of the yellow radio dial was this big green evil eye, which was actually a tuning eye, an aid to sharper station selection. The narrower the eye’s wedge-like beam, the sharper (more accurate) the tuning.

While my parents preferred listening to the news and President Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, I liked to listen to afternoon entertainment such as Jack Armstrong, Henry Aldrich, The Lone Ranger, and Got-em-Tennessee. Sunday night was always family radio night. The comedic fare began with Jack Benny and continued with Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Fred Allen, and Judy Canova.My bedtime on school nights was still 7:00 p.m., so weekday evening radio was out of the question for me. On Fridays and Saturdays it was 8:00 p.m., so I was usually shuffled off to bed in mid-Inner Sanctum. I could hear the sound through the wall of my bedroom next door, but it was so muffled, I couldn’t make out what was happening or even playing. The same was true in the summertime when the rest of my family sat on the screened-in front porch, and their voices drifted in through the open bedroom window. Boy, was I nosy! Was I ever missing something!

There were two houses next door to us on the left, one on the street and the other fifty feet behind it. Each of the two Catholic families living there had a son—one named Robert McCaulif and the other, Buddy Baker. They were my age and a year older. They never allowed me to be their friend, but it wasn’t for the lack of my trying and, as time went by, I learned it was because they knew I was Jewish. In my early efforts to join their exclusive clique I was told I’d have to go through some hazing to prove my worthiness. The paddling, the tainted tasting, and the leg lock, wrapped around a basement stanchion, I endured, but I refused to swear on the Christian testaments or recite prayers from them. Needless to say, I did my best to avoid them thereafter. It was my first exposure to anti-Semitism, yet I don’t know what made me feel so strongly about the ultimate price they tried to impose on my offer of friendship.

Perhaps it was my early Sunday School training at Temple Mishkan Israel. Looking back now, I’d say I acquired a fine Jewish education and strong Jewish identity. I’m guessing the temple was between five and six miles from our home—in other words, the other side of downtown. At one point my brother, George, and I frequently walked the whole way, stopping here and there to pick up his older classmate friends. When George was confirmed and had moved on to other Sunday activities, I rode the trolley to the end of the line and walked another two blocks to religious class.

End-of-the-line meant the trolley reversed direction without turning around, so the angled pole contacting the overhead wire at the rear had to be reined in, and the pole at the front let out. While the conductor did this, I often helped to reverse all of the seat backs, so the passengers could ride face forward. It was a job that made me feel useful.

I joined the YMCA primarily to be able to swim at their pool. It cost 25 cents a month to join, and I was assigned to a group of eight boys led by a Yale University divinity student. Right from the beginning everyone knew I was Jewish. We met twice a month for discussion, once a month to swim, and once a month for sports. At these discussion groups I learned a fair amount about the Christian religion without having to give an inch on my own faith. It turned out to be a decent learning experience. In fact, I acquired Bob Altier, Clark Caugland, and Louis Gramaldi as friends for the remainder of my time living on Spring Street.

In the summer of 1941 we moved from Spring Street to 211 Maple Street on the northeast corner of Brownell Street, a few blocks from the main artery of Whaley Avenue in western New Haven. It was a slate roofed, all white, three-story house in which we initially occupied the second and third floors and rented out the first floor. Later we rented out portions of the third floor. There was also a two-car rental garage—we still didn’t own a car. All of the rooms branched off of a long hall that began with the bathroom at the rear of the house and ended in a house-wide living room. A kitchen and dining room lay to streetside of that hall and two bedrooms lay to the other side of it. The new neighborhood brought with it a fresh set of friends. I started Augusta Lewis Troup Junior High School (grades seven through nine) that fall. The new school district meant a fully integrated school, a novel yet broadening experience for me, for I had not encountered black students before.

I turned nine in September of 1941, the year the European rumblings began to reach our local media. Hitler was on the move and countries were falling before him. I knew this meant some dread to my parents, but I believe I was quite oblivious to these happenings. After all, I was just a kid. My awareness was something that would soon change.

| Go to top of page | |