Magic Island Literary Works

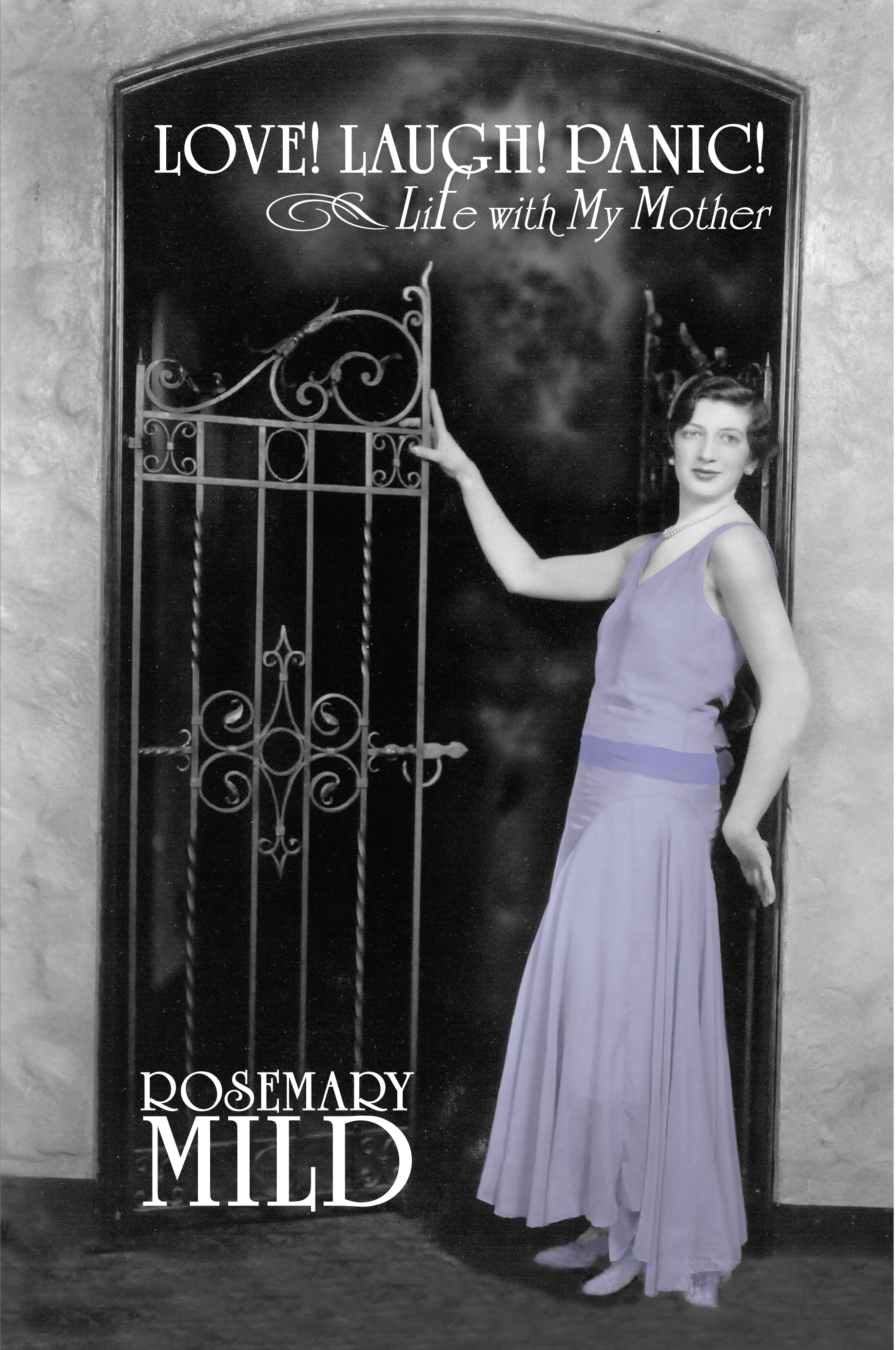

Magic Island Literary Works A Dynamic Roller-Coaster, Mother/Daughter Relationship by Rosemary Mild.

| Home | Select Books From Spread | Authors | Contact Us | Author Interviews | Monthly Blog |

Don't we all have mixed emotions about our mothers? But how many of us have a mother like Rosemary's: multi-talented, yet super-tough to live with? Luby Pollack was a widely published journalist, popular book author, and even an artist of sorts. She sometimes had a daunting role to play. In the delivery room during Rosemary's birth, her psychiatrist husband ordered her not to make any noise during labor—it was "unseemly for a doctor's wife." Rosemary Pollack Mild started to write a book strictly about herself, but that didn't go so well. She discovered that Mother popped up on every page. Looming. Encouraging. Warning. Always the Protagonist, the Star, the Heroine, the Antagonist, and sometimes the Villain from the viewpoint of a loving but ornery daughter. |

ISBN:978-0-9838597-7-2. Magic Island Literary Works |

To let Rosemary know what you think of Love! Laugh! Panic! Life with My Mother

E-mail us at: [email protected]

|

|

Buy autographed trade paperbacks at author's discount price: |

Love! Laugh! Panic! Life With My Mother, Photos

Click here to see OUTSTANDING REVIEWS BELOW

| Enjoy a sample chapter of Love! Laugh! Panic! Life with My Mother | |

Chapter 1

Urgent! Send Money!

Love! Laugh! Panic! Life with My Mother

In 1932, my parents, Luby and Saul Pollack, spent their honeymoon in London. My father had graduated from medical school and completed his residency in psychiatry. Afterward, he landed a position for several months of postgraduate work in neurology at Queens Hospital.

From London a telegram arrived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for Luby’s parents, Harry and Elizabeth Bragarnick. “Urgent! Wire $500 immediately.”

Imagine what $500 was worth in 1932. Harry and Elizabeth were panic-stricken. Their daughter had been frail and sickly during a great deal of her childhood. Had some terrible illness overtaken her? Did she need an operation?

When the honeymooners returned from London, the truth came out. Luby had spent the $500 on a custom-designed set of Royal Worcester china. Twelve place settings, plus soup bowls and salad plates, cups and saucers, large platters, and a gravy boat. The china was exquisite. White with a wide border of rich, deep blue. An elaborate pattern of gold loops danced through the border, decorated at intervals with tiny hand-painted orange dots. Yes, handpainted. Harry was furious, but his fury didn’t last long. Luby was the favorite of his three daughters; she was the most like him, with an incisive mind and flamboyant, charismatic personality.

Chapter 2

Goodbye, Dolly

For my sixth birthday party, in the summer of 1941, my mother hired a horse with a man to lead us on rides around the neighborhood. Not a pony, mind you, but a tall, colossal horse. It was also on my sixth birthday that my parents gave me my first doll. Smiling and rubbery, with kinky yellow hair, it came tucked inside a beige wicker buggy. After my guests had gone home, I took my doll for a walk, contentedly pushing the buggy for blocks and blocks through our Milwaukee neighborhood, not having the slightest notion of where I was going, nor caring. The tree-shaded sidewalks were silent, and I was alone and happy in the world. Suddenly, a police car pulled up beside me and a huge officer climbed out. “I’m Sergeant Henderson,” he said. “Your mother sent me to bring you home.” I couldn’t figure out why. What had I done wrong? He gently piled me and my buggy into the back seat of his cruiser.

My parents were frantic because I had been gone for hours. “Go to your room!” Mother shouted. “Some gratitude for your birthday party!” This was not just Time Out. This was Year Out, Decade Out. It probably wasn’t more than an hour, but from then on, I despised dolls and buggies.

Mother lavished riches on me because as a child she didn’t have any. She arrived at Ellis Island from Russia when she was five with her sister and parents. In first grade, Mother had only one dress. It had a white collar and cuffs, which Grandma Elizabeth washed and ironed each night and sewed back on so little Luby would look clean for school.

Mother never had a doll, which explains why she lovingly bought me one for Chanukah when I was nine. I thanked her loudly, but grateful I wasn’t. I had never gotten over the Sixth-Birthday Doll-Buggy Disaster. This new doll was aristocratic, almost two feet tall, with porcelain body and face, shiny auburn locks, and blue eyes with curly black lashes. It came in its own wooden cradle and was so important to Mother that she even named it: Penelope. A name I hated. My doll lay there forlorn and unappreciated for two years until one day I picked it up. I was curious about the arms and legs, how well they’d move. Not well, I discovered. In the split second it took Penelope to bat her lashes at me, I twisted off her right leg. Was it a Freudian accident, a subconscious rebellion against my mother? I’ll never know. Toys do get broken, more often than not.But this little act of destruction terrified me. I couldn’t just tell her the truth. So I laid Penelope back in her cradle and set the leg firmly in place so she’d look whole again. For the next three months, every time Mother came in my room I held my breath. I willed her not to notice. But of course one day she did—because the right leg was now a bit longer than the left. To my surprise, she didn’t scold or yell.

“What happened?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I whimpered.

Penelope meant so much to Mother that she carted her off to the doll hospital in downtown Milwaukee for hip replacement surgery, very successful, I’m happy to report. Nevertheless, I wasted no emotion over it.

Mother knew better than to ever buy me another doll. But she did make me one: a black yarn doll with a red yarn dress that you could take off and put on. Its eyes are embroidered in brown and its hair is arranged in tiny pigtails all over its head, secured in red yarn ribbons. Back then it was called a pickaninny doll—politically incorrect today, of course. Mother made it out of squares of yarn woven on a frame with little steel spikes. She let me make some of the squares, and I had a grand sense of accomplishment weaving the yarn in and out. She even taught me to finish off the squares so they wouldn’t unravel.

Today the doll sits high on a shelf at home, one of my treasures: a symbol of my mother’s love for me and her endless desire to make a place for dolls in my life.

| Read outstanding reviews ofLove! Laugh! Panic! Life with My Mother | |

Reviewed by

T

| Go to top of page | |